One of many fascinating features of our mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) is that they are designed to stop growing on contact. In other words, when MSCs touch, they stop multiplying, or making copies. Embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) don’t do this. Why is this significant? Because it’s this inability to stop growing on contact that presents the concern for tumor development in these other stem cells. So, today, as we continue in our “Let’s Talk Stem Cells” series, we’re talking about those mesenchymal stem cells that stop growing on contact, a natural phenomenon known as contact inhibition. Let’s first define the stem cell types mentioned above.

Defining Stem Cell Types

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are cells that make a baby as it grows in the womb. They are pluripotent, which means that they can turn into most any cell type—ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm—in the human body. ESCs can make an unlimited number of copies of themselves and are therefore very potent; however, besides the ethical issues that have plagued the use of ESCs for research purposes, ESC use is also associated with tumors.

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) were once normal adult cells in which genes were altered to trick the cells into acting like pluripotent embryonic cells. Why? To make these stem cells immortal so they’ll grow forever, not a wise idea in our book.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are adult stem cells (adult stem cells are stem cells after the embryonic stage, so after birth, and throughout life). They are multipotent, and they can differentiate into many mesodermal cell types, such as osteoblasts (bone cells), adipocytes (fat cells), myocytes (muscle cells) and chondrocytes (cartilage cells). We covered differentiation in a recent “Let’s Talk Stem Cells” post.

Mesenchymal Stem Cells Know When to Stop Growing

In their normal state, MSCs in the human body will eventually stop growing. This inherent safety mechanism in MSCs is known as contact inhibition. This means, quite simply, that once the stem cells touch each other, they get the signal to stop growing. Neither the embryonic nor the induced pluripotent stem cells share this same safety profile, which is the concern for overgrowth and aggressive tumor development in these other stem cell types. Learn more about this in Dr. Centeno’s brief video below:

More on Contact Inhibition

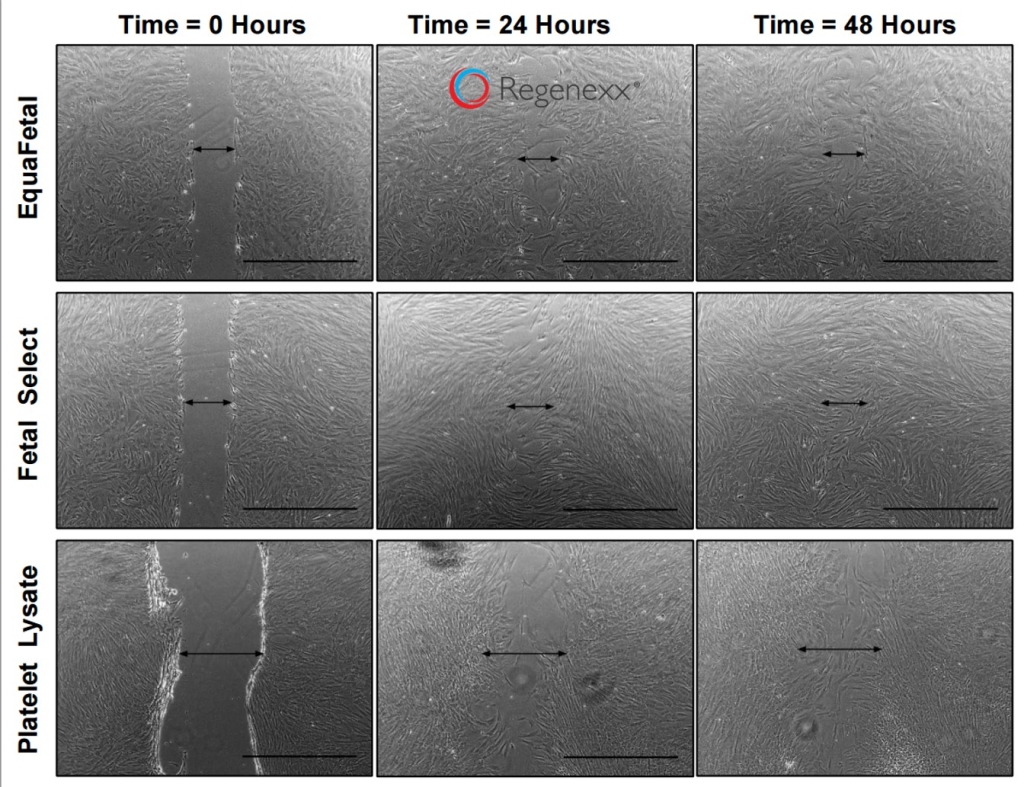

The image below demonstrates a “scratch test” done in our advanced research lab.

In the left column, a scratch has been made through the mesenchymal stem cells that had attached to a plate. The cells were left to grow (each scratch sample in a different media) for two days. In all three cases, the MSCs closed the scratch gap. How did this work?

MSCs like to spread out and cover a surface. As long as they are not touching, they will proliferate, divide, and continue to look for new space. When the space is filled up, and they begin to touch each other, that contact inhibition kicks in, and they stop growing. You can read more about this at this link: “How Do Stem Cells Heal.”

Our mesenchymal stem cells are not only hard-working multitasking machines, they also come with a protective mechanism—contact inhibition. This allows stem cells to stop growth on contact with other MSCs. Knowing when the job is done sets MSCs apart from other stem cell types and makes them the ideal source for orthopedic stem cell treatments.