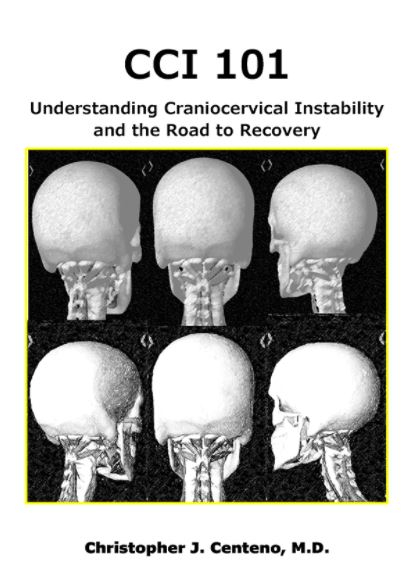

I have seen CCI patients from all over the world for decades, so I am a craniocervical instability specialist. This morning I’d like to review the case of an EDS patient who never should have had upper neck fusion surgery. Why? To help CCI patients understand what to avoid.

EDS and CCI

Some of the more common patients seen by a craniocervical instability specialist are patients with hEDS (Ehler-Danlos Hypermobility syndrome) that have craniocervical instability (CCI). These patients have too much movement in many joints, not the least of which is their craniocervical junction (CCJ). In fact, CCI is not uncommon in this patient population.

My Patient

As a craniocervical instability specialist, I first began to see these patients decades ago. However, what’s new these past few years is that I have seen a significant number of patients with complications from C1-C2 fusions. So it’s clear to me that these procedures are becoming more commonly used.

It’s always a little emotionally challenging when I see a CCI patient about the same age as one of my kids whose life has been destroyed by overly aggressive surgery. My patient’s problems began with TMJ, which was being managed reasonably well through therapy. However, at some point, she was told that she had craniocervical instability and was sent to a neurosurgeon. That visit resulted in a C1-C2 fusion procedure which is where this story starts to become dangerously unraveled.

C1-C2 Fusion

As discussed above, as a craniocervical instability specialist, one of the most common surgeries that I see CCI patients getting these days is a C1-C2 fusion. There are a number of types of techniques including from the back with screws going through the joint (trans-articular), from the back with rods and the screws placed at C1 and C2 (Goel and Harms Technique), and from the front with screws or a plate. The goal is to make this area not move as an attempt to “fix” the craniocervical instability. However, this procedure has severe risks as I’ll show, so it should only ever be used as a last resort when the patient is completely disabled.

My Patient’s Botched C1-C2 Fusion

How disabled was this young woman prior to surgery? She had symptoms due to CCI and had activity restrictions and self-imposed restrictions. For example, while she attended a college with a big football team, going to games was out of the question due to the fact that she could be inadvertently bumped. However, nothing had prepared her for how much worse she would get after her surgery. Let’s dig in.

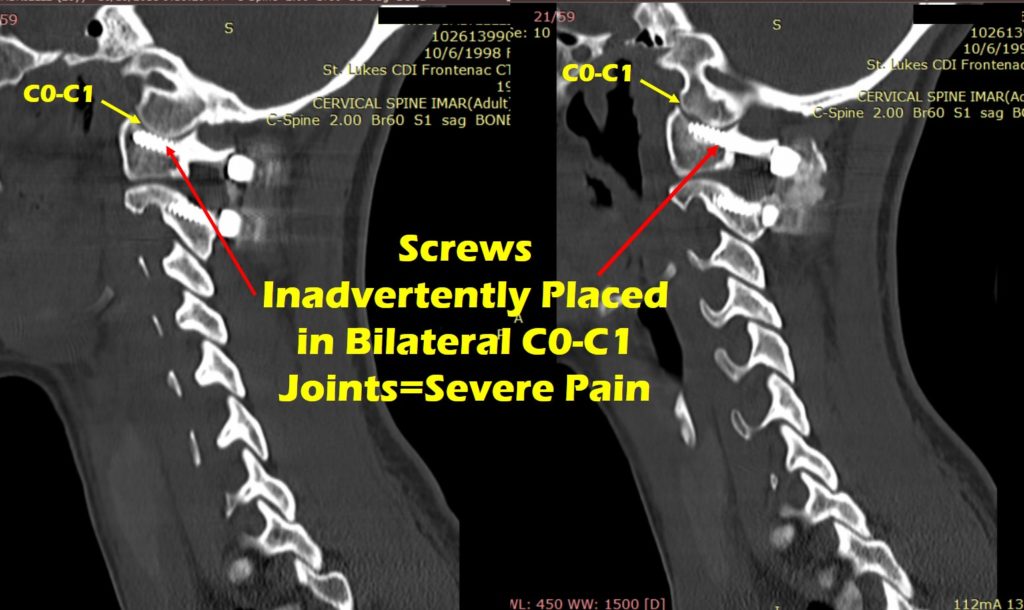

When she awoke from the procedure, her pain was much worse. In particular, she noticed a scraping sound at the base of her skull when she went to look up or down. Regrettably, her surgeons didn’t take this too seriously and it took them many months with 9/10 head pain before they took this CT scan:

This shows that the surgeon placed both of the screws that were only supposed to go only through her C1 bone too high, so they inadvertently placed them through the C0-C1 joint. Why is that a big deal? This is the joint that nods your head. When a screw this size is placed through a small neck facet joint, it destroys the joint surface and cartilage. In this case, literally every time she moved her neck, the screw was scraping off more cartilage. Somewhere in there one of the screws broke as well.

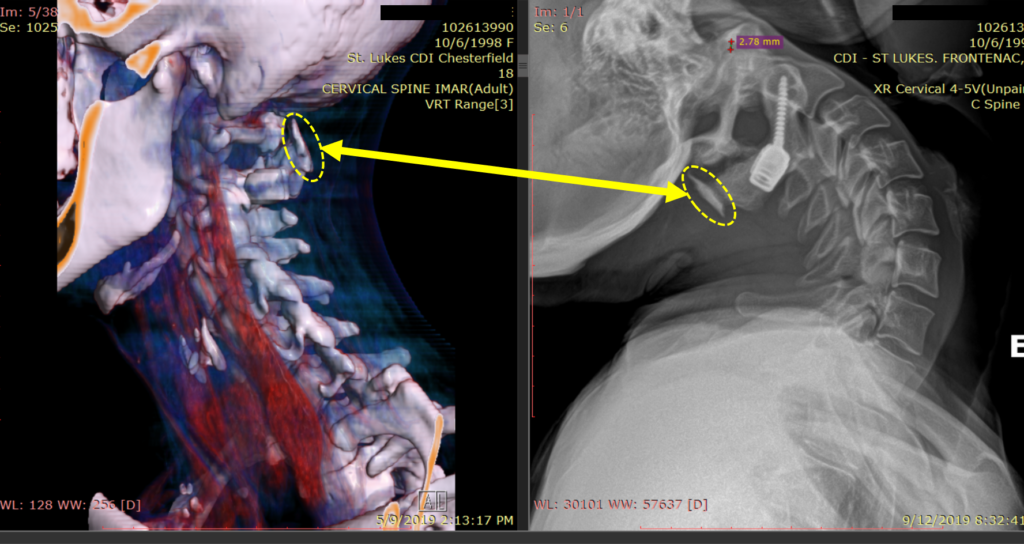

When the family finally got this image, they quickly found another surgeon, trying to find a craniocervical instability specialist who could fix the problems created by the first procedure. That surgeon decided to remove the C1 screws that were misplaced and then to explore whether the fusion mass was intact. The back of the fusion mass is seen in the image below in the dashed circle (3D CT Scan to the left and x-ray to the right). The purpose of a fusion mass is to add bone so that the C1-C2 vertebrae grow together and thus reducing the reliance on the hardware.

However, after this procedure, she began to get blackout or grey out episodes when she turned her head. The pain also got worse and she also started to experience TIA type episodes where her face or other areas would go weak. Suffice it to say that the second procedure, instead of helping, made things worse.

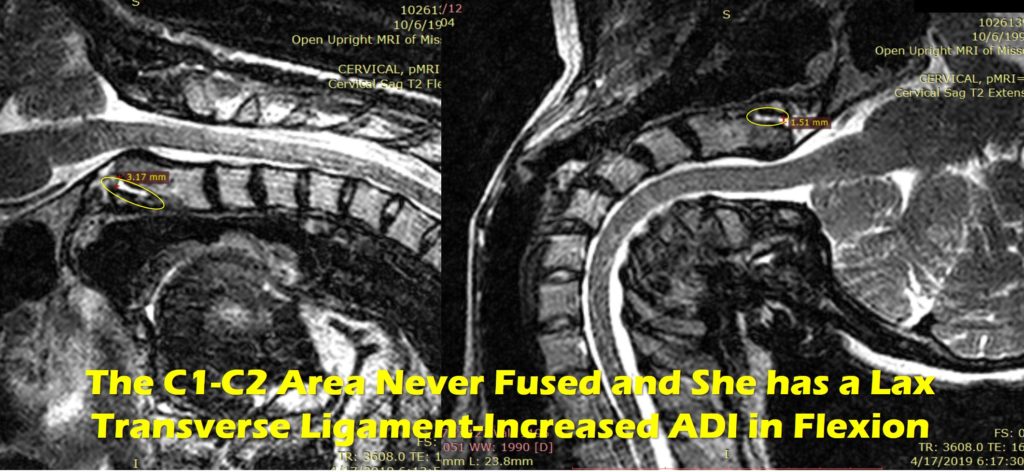

So was C1-C2 really fused? Nope. The flexion-extension MRI below shows that the distance between the front of the C1 bone and dens part of the C2 bone (ADI or Atlanto-Dental Interspace-dashed circle here) gets greater in neck flexion, indicating continued C1-C2 (atlantoaxial) instability:

Should This Have Been Done?

I feel very strongly that the initial procedure should never have been attempted by any surgical craniocervical instability specialist in a functional young woman of college age who could manage her symptoms. The substantial risk of this procedure far outweighed any benefits. In addition, all fusions cause ASD or adjacent segment disease. For example, since C1-C2 is responsible for half of the rotation of the head, in someone with normal ligaments it will eventually damage the C0-C1 and C2-C3 joints. In someone with hypermobile ligaments like an hEDS patient, all of that is much worse. To learn more about ASD, see my video below (this is about lumbar, but the same concepts apply to the neck):

This type of upper cervical fusion procedure was designed for patients who have severe life-threatening fractures of the upper neck bones. In a handful of CCI patients with damaged or loose ligaments who are completely disabled, it may be appropriate. In an hEDS patient who is otherwise able to function at a high-level, it should NEVER be done. Meaning this is not an elective lifestyle procedure to improve function, but a rescue procedure that has lots of potential complications and that can spin out of control. Regrettably, it’s obvious to me, based on the complications that I see, that we have an increasing number of patients who are using it to reduce symptoms and improve function rather than as a court of last resort for the severely disabled.

What Can Be Done Now?

Regrettably, these procedures have backed this young woman into an unenviable corner. As a craniocervical instability specialist, here are the many layers to her problems as I see them:

- What’s causes the blackout and TIA (ministroke) like episodes when she turns her head? This could be the fusion mass putting pressure on the vertebral artery and cutting off blood supply to the back of her brain. Her prior doctors tried to work this up, but she can’t stay in that position for very long, so no standard dye-based imaging test will work. We will try real-time color doppler imaging of the vertebral artery this week.

- Can the destroyed C0-C1 joints be helped? I have seen a few other patients who had the same thing happen, but I was unable to help. The severe scarring caused by these procedures and the change in the position of the anatomy makes it very hard to get stem cells into these joints. For example, this week, I was able to inject 5/6 of the C0-C3 facet joints, but the left C0-1 joint remains tough to access. I’m also unsure if these procedures will help or if the joints are too far gone. She may need to go to our licensed Grand Cayman facility where we can grow cells to greater numbers in culture. Even then, there are no guarantees we can help these severely damaged joints.

- It’s likely that the occipital nerves as they pass behind the C1-C2 joints were sacrificed during the procedure or damaged and/or are now encased in scar tissue. It’s possible that trying to inject around these nerves using precise ultrasound guidance to break up the scar tissue and place healing growth factors or stem cells may help. If that doesn’t work, she may need a nerve stimulator placed to help the headaches by blocking the signals from the damaged nerves.

- She’s still unstable at C1-C2, so our novel PICL procedure focused on tightening down the lax transverse ligament may help.

- Finally, an even more invasive skull to C2 fusion with large plates could be needed, but her parents are obviously skeptical that a third procedure will help versus dig the hole deeper.

The upshot? As a craniocervical instability specialist, since I have a daughter her age in college, this case was emotionally trying for me. To see a young life that was previously “getting by” wrecked by an overly invasive procedure is tough. It’s even tougher to know that unlike many CCI patients I treat, I may or may not be able to help this poor young woman.