C1-C2 fusion is all the rage among patients with CCI. So what is it and what are the side effects? Should you get a C1-C2 fusion? Let’s dig in.

What is Craniocervical Instability (CCI)?

Craniocervical instability (CCI) is when the upper neck levels of the spine are unstable (1). This is usually C1-C2, but can also be C0-C1. There are a number of strong ligaments that hold this area together which can be injured or loose and there are a slew of measurements used to determine if CCI is present. Common symptoms can include headaches, dizziness, imbalance, upper neck pain, visual disturbances, rapid heart rate, and various pains elsewhere, just to name a few.

What is C1-C2 Fusion? Why Is It Done? Are there Different types?

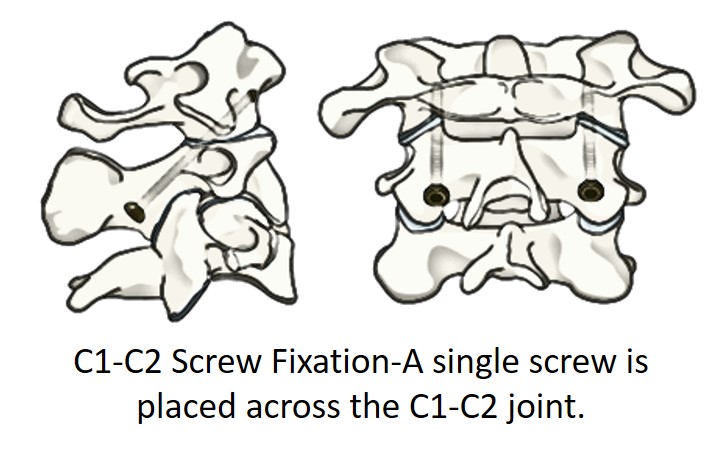

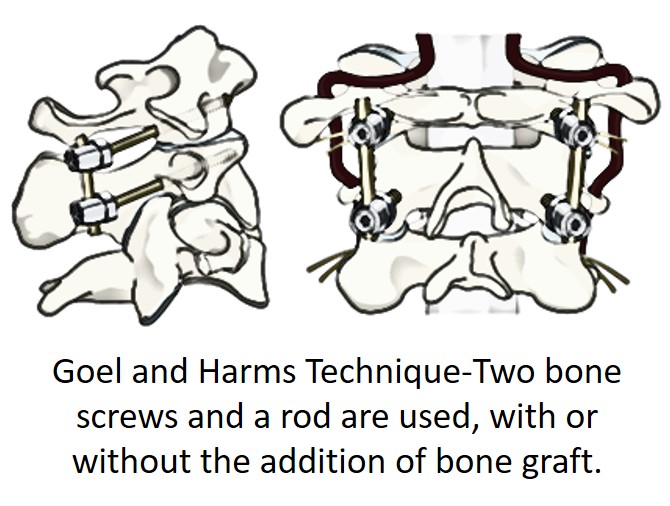

C1-C2 fusion means using screws, rods, or bone to make sure that the C1-C2 joint doesn’t move. While the most common reason this rare procedure was performed used to be because of an upper neck fracture or severe ligament rupture, these days more of these procedures are performed in patients with ligament laxity leading to upper cervical instability. This is where this review of C1-C2 fusion will focus. The two most common types of C1-C2 fusion that I see in patients I consult on are posterior screw fixation (Magerl Technique or C1-C1 trans-articular screws). In the C1-C2 screw fixation, a single screw is placed across the joint as shown to the left. The positives for this technique are that it disrupts less of the stabilizing muscles at the back of the upper neck, which are critical for stability. Since the goal of the procedure is getting the normally mobile C1-C2 joint to grow together and become one solid mass of bone, when this doesn’t happen, it’s called a non-union. A bigger issue seems to a risk of vertebral artery injury (2). The Goel and Harms technique (right) is more extensive than the C1-C2 screw fixation. Here two screws are placed into the bone and a rod system is used to hold the C1-C2 joint. Bone chips from the patient are often placed around the rods to help provide stability as the bone grows. The big downside with this approach is the extensive muscle damage that’s required to get all of this hardware in place. Other risks include again, damaging the vertebral artery. In addition, many surgeons will also sacrifice the C2 nerve, which can lead to chronic pain.

C1-C2 Fusion Risks

Now that these procedures are being performed for non-life threatening injuries like ligament laxity, the risk-benefit ratio is different. For example, when a patient with an upper neck fracture may die or become a high quadriplegic if the fracture isn’t stabilized, the risks allowed for the surgery can be quite severe and the risk versus benefit equation still makes sense. However, now that these invasive procedures are being performed for patients with loose upper neck ligaments due to damage or congenital problems like EDS, the risk-benefit bargain can be a bit off. Let me show you what I mean.

Nonunion

One of the big risks of any fusion surgery is that the joint being fused never actually grows together. For these procedures, accurate information that applies to adults is hard to find, as many of these surgeries are performed on children with congenital abnormalities. However, at least one author states that nonunion rates can be high with these techniques (5). However, there’s nothing like a good case report to make complications personal. Katie is a twenty-something I treated several years ago. She had a C1-C2 screw fixation performed for CCI after a DMX showed too much movement at C1-C2 and nothing else was helping. Regrettably, the joint never fused, leaving her with new strange movements of the C1-C2 joint as it now pivoted around the screw going through it. The joint was also damaged by the screw and still moving, making her headaches worse and not better (pain from the C1-C2 joint refers to the head). She was also not a good candidate for our PICL injection procedure due to the surgery. Through injections of PRP into the C1-C2 joint, we were able to get the joint to fuse, but she also had damage to the nerves and extra force across the C0-C1 joint leading to new pain there. These areas were treated with platelets and stem cells with some improvement.

Misguided Screws

A big issue we’re seeing in the clinic is the fact that these screws placed into bone are hard to guide. Hence, they can inadvertently reach places that can damage structures. For example, the screw can hit the vertebral artery and damage it, end up hitting and damaging nerves, and even destroy the C0-C1 joint. Since these screws are large, what they hit is usually obliterated. The vertebral artery runs through the neck bones and this upper neck area. It supplies blood to the back of the brain.

The good news is that most people have one on each side, so losing one vertebral artery can often be compensated for by the other. Realize though, that destroying one of these arteries with a big screw is still a very bad thing. For example, in an older patient, this could lead to a stroke (blood clot or other debris floating into the blood supply of the brain). This happens 4-10% of the time with upper cervical fusion (2,4).

Damage to the upper spinal nerves can also happen (3). The most common nerve injury is to the C2 spinal nerve (3). This supplies the back of the head, so damaging it can lead to chronic headaches. As discussed above, the C2 spinal nerve is also sometimes sacrificed in the surgery itself. That means it’s taken out by the surgeon because it’s in the way of the desired screw placement. This can also lead to chronic head pain about 1/3 of the time.

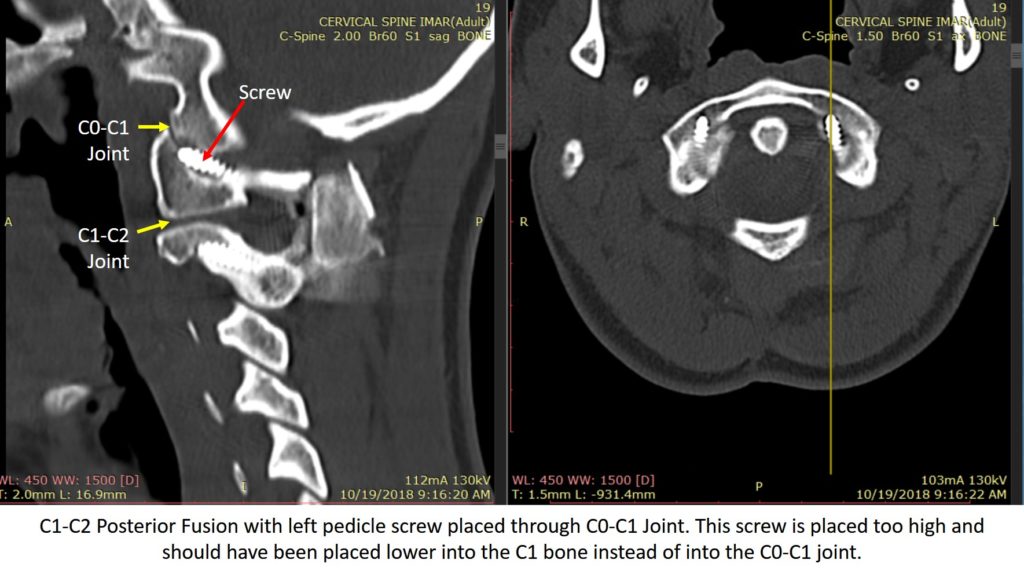

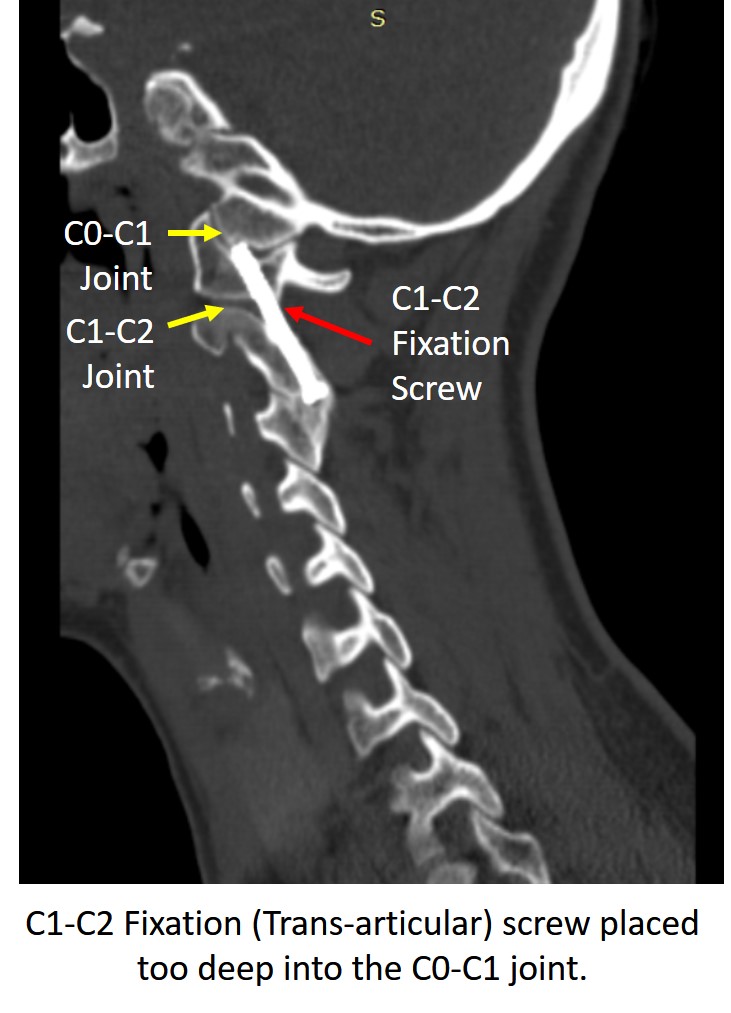

The destruction of the C0-C1 joint is also possible and frankly, one of the most common complications I have seen. Here the screw is placed too high and travels through the C0-C1 joint, which destroys the joint. This means that the screw causes arthritis in the joint, which is bone and cartilage damage. So the C0-C1 joint becomes a new source of pain. This joint also causes headaches at the back of the head.

C0-C1 Joint Damage Case Reports

The most common complication I see with these C1-C2 fusion surgeries is that the screw goes into the C0-C1 joint. This is a BIG problem. Why? This destroys the cartilage and bone in the joint and leads to instant arthritis. Since this joint commonly refers pain to the head, it can cause instant and new pain at the base of the skull. Let’s go over two patients that were sent to me after this happened.

The first patient is Rosalyn, who was a student at an elite university. She was diagnosed with CCI due to a car crash and had moderate instability on her DMX and evidence on MRI of alar/transverse ligament injury. She underwent C1-C2 screw fixation where a screw was placed through the C1-C2 joint to fuse it and to reduce her instability. Regrettably, on one side that screw was placed too deep and she woke up from surgery with new pain right at the base of the skull on that side. This worsened over the ensuing few days and when she also reported a “scraping sound” at that spot when she went to look up or down. That was the screw scarping off some of the cartilage in the C0-C1 joint. She then underwent subsequent surgeries to remove the screw, but by then she had two problems. The first was severe arthritis in this joint and disabling new headaches from that damage. The second was that the two surgeries destroyed most of the critical stabilizing in this area, which only increased her instability. We tried to perform a PICL injection procedure and injected stem cells into the C0-C1 joint to aide repair, but this only helped minimally as the damage from the screw was extensive. The good news is that as far as I know, she was able to get enough relief to finish college, but the bad news is that she continues to have this disabling pain to this day. The second case is also of a young woman, but her issue was a loose C1-C2 level due to EDS. She had a modified Goel and Harms technique C1-C2 fusion. On the right, you see the screw was placed too high into the C1 bone and ended up inside the C0-C1 joint. She reported immediate pain at that site after surgery. However, it seems that she wasn’t taken seriously and it took 3 months to get this film showing the problem. The screw was eventually backed out, but then the mass of bone placed in this area to promote fusion fractured, leaving her without any bone stabilization. On a positive note, all of the new scar formation from the surgery provided some stability, but the recommendation is still to fuse her from C2 to the skull, which she doesn’t want. Hence, I will be treating her with bone marrow concentrate (a same-day stem cell procedure) to try to help this joint heal and to promote the fusion mass to fuse again.

Adjacent Segment Disease

Adjacent segment disease (ASD) is the bane of every fusion, making the biggest hit to its success rate. ASD happens because all spinal levels are built to move just a little bit. When that movement is stopped due to fusion, the levels above and below take too much force and can develop degenerative arthritis and breakdown. Here the C1-C2 joint is responsible for half of all of the rotation of the head on the neck, so fusing it dramatically increases force both on the C0-C1 and C2-C3 joints above and below. Meaning that over time, you can expect these levels to break down in most patients.

The Other Side of the Argument

There are patients who really need this surgery. In fact, I can remember one patient from more than a decade ago who had life-changing results. Having said that, I’m seeing much higher complications and side effects than have been reported by surgeons in the literature. Hence, trying less invasive procedures, such as our non-surgical treatment for craniocervical instability, first just makes common sense. The upshot? Upper cervical fusion is not a routine spinal surgery. It’s much higher risk than the average procedure due to the vertebral artery as well as the other problems I’ve shown. In addition, I’ve seen far too many screws inadvertently placed into the C0-C1 joint which destroys it and often causes new pain. So while there are a handful of patients that really need this surgery, it’s always a good idea to try less invasive procedures first before fusion.

___________________________________________________

References: (1) Mathers KS1, Schneider M, Timko M. Occult hypermobility of the craniocervical junction: a case report and review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011 Jun;41(6):444-57. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3305.

(2) Gluf, W. M., & Brockmeyer, D. L. (2005). Atlantoaxial transarticular screw fixation: a review of surgical indications, fusion rate, complications, and lessons learned in 67 pediatric patients, Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine, 2(2), 164-169. Retrieved Jan 8, 2020, from https://thejns.org/spine/view/journals/j-neurosurg-spine/2/2/article-p164.xml

(3) Myers KD, Lindley EM, Burger EL, Patel VV. C1-C2 fusion: postoperative C2 nerve impingement-is it a problem?. Evid Based Spine Care J. 2012;3(1):53–56. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298601

(4) Schroeder GD, Hsu WK. Vertebral artery injuries in cervical spine surgery. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4(Suppl 5):S362–S367. Published 2013 Oct 29. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.120777

(5) Ghostine SS, Kaloostian PE, Ordookhanian C, et al. Improving C1-C2 Complex Fusion Rates: An Alternate Approach. Cureus. 2017;9(11):e1887. Published 2017 Nov 29. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1887