Hip resurfacing may sound like a kinder, gentler alternative to hip replacement, but is it? There may be fewer steps to the surgery, but it is still highly invasive and, according to research, is riddled with many serious problems of its own. Today we’re going to define the difference between hip resurfacing and hip replacement, and then we’ll review the literature.

Understanding the Difference Between Hip Resurfacing and Hip Replacement

It’s important to first get a basic understanding of the hip anatomy. The hip is formed at the junction of the pelvis (or the “hip girdle”) and femur (the upper leg bone). On the pelvic bone, there is a shallow socket called the acetabulum where the ball-shaped femur head naturally fits, making the hip one of only two ball-and-socket structured joints in the human body (the other being the shoulder). The acetabulum is lined with protective cartilage and the rim is of the acetabulum is lined with a further protective tissue called the labrum. The hip is a large joint that is precisely designed to perform complex movements, such as rotational motions, most other joints aren’t capable of.

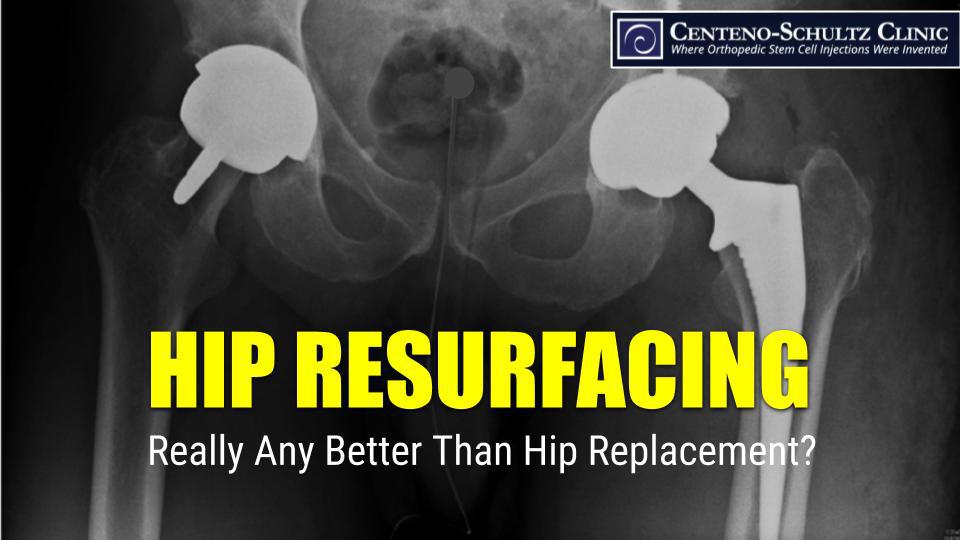

During hip resurfacing, the cartilage and labrum are removed from the acetabulum in the pelvic bone. A manufactured socket, typically made of metal (can also be made from polyethylene), is then cemented into the socket. This new socket is then lined with material that acts as the new cartilage for the hip joint. The femur head is then resurfaced, or cut back. A ball-shaped cap, which will then fit into the replaced acetabulum is then placed over this resurfaced portion of the femur.

During a hip replacement, the same procedure is followed for the acetabulum, but on the femur side, the head is fully amputated. A hole is drilled into the middle of the femur, and a metal rod-like device is fitted into the hole. A metal head is then attached to the rod and acts as the ball portion of the hip.

Hip resurfacing is considered less extreme because the femur head is not completely removed, but it’s still riddled with complications, some of which are more severe than those in hip replacement.

Hip Resurfacing Has Its Own Problems

Some of the literature does indeed show fewer problems with hip resurfacing. Unfortunately, there are many other cases in which it fares much worse. Let’s take a look at a few.

Devices Shed Metal Particles

Hip resurfacing materials are known to shed metal particles, and the problem has been addressed in warnings from the FDA. When compared directly to patients with hip replacement, those who had hip resurfacing surgery were found to have cobalt and chromium metals in higher amounts in their blood as well as alterations to the visual function areas in their brain.

Hip Resurfacing Associated with Earlier Failure

Many with femur heads that are smaller, such as women and smaller-structured men, experience poorer outcomes than their hip replacement counterparts. In particular earlier failure of the devices, by as much as five years, was found in those with hip resurfacing. And for patients under 55 years of age, the rates of revision within five years were even worse—almost twice as high as hip replacement.

Hip Resurfacing Associated with Pseudotumors

Pseudotumors (tumor-resembling growths due to fluid buildup, inflammation, or other tissue reaction), known to be common following hip replacement, are also an unfortunate side effect of hip resurfacing, occurring in as many as 28% of those who undergo the surgery. Pseudotumors are associated with poorer outcomes after surgery, which includes more pain and less function.

We certainly aren’t suggesting that hip replacement is a better solution; we are simply pointing out that considering hip resurfacing as a kinder, gentler solution with fewer associated problems isn’t panning out in the research. Avoiding surgery altogether should be the primary goal, and at the Centeno-Schultz Clinic, in all by the most extreme cases, this can typically be accomplished with advanced image-guided injections of a patient’s own stem cells or platelets.