Today we’re seeing more and more orthopedic surgeons fusing multiple back bones at once. Instead of a one-level lumbar fusion, which fuses two bones together, they’re doing two or three levels, which fuses three or four bones together. We probably don’t have to state the obvious here, but the more levels that are permanently joined together in a back fusion, the more damage that is caused to the adjoining back bones and other surrounding structures that attempt to compensate for the lack of mobility in the fused section of the spine. How often does this happen? We’re going to see what the research says, but first, let’s take a look at the anatomy of the back and define spinal fusion.

Understanding Back Anatomy

The spine consists of a vertical column of bones called vertebrae. It begins at the base of the skull and spans the full length of the back, all the way to the tailbone. There are five segments, which include the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacrum, and coccyx. So when you see on a report, such as an MRI “L5,” that is the fifth bone in the lumbar section of the spine. The vertebrae not only provide structural support, but also serve as protective housing for the spinal canal, the bundle of nerves that connects to our brain and supplies every part of our body. Discs live in the spaced between the vertebrae and cushion the bones and act as shock absorbers. The spinal column is made for movement, and as such is a very flexible structure.

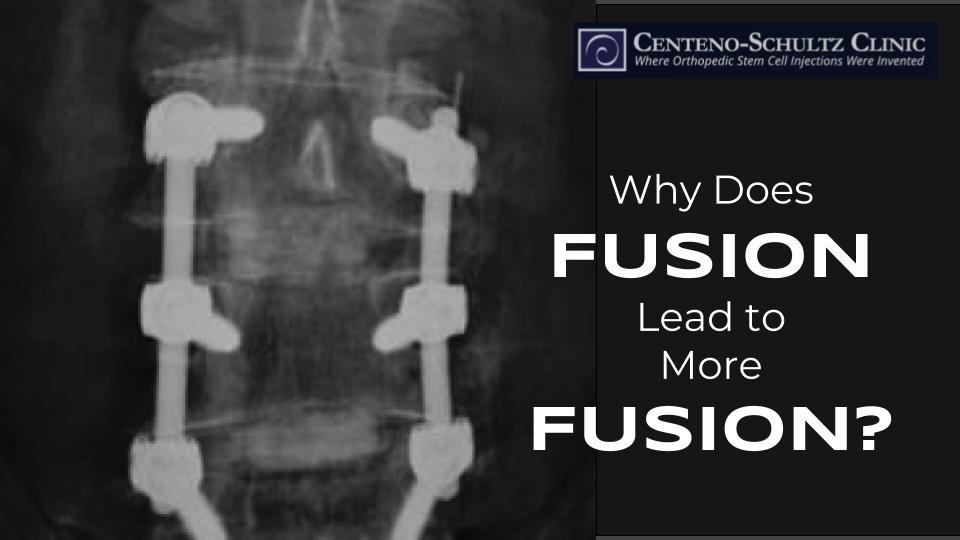

What Is a Back Fusion?

A back fusion first involves removing a disc between two vertebrae. So if the levels involved are the L5 and S1 vertebrae, this means the disc is removed from between the fifth lumbar bone and the 1st sacral bone. The two vertebrae are then forced together via hardware, such as screws, or sometimes bone grafting is used. The two bones then grow together and fuse into one solid bone structure. A two-level fusion includes three vertebrae; a three-level, four vertebrae; and so on. So while the spine is designed for flexibility and motion, a spinal fusion is designed to permanently stop movement.

The Problem with Fusion? Adjacent Segment Disease

When one vertebral segment becomes immobile, the segments above and below the fused segment will jump in and try to take on the extra forces. When these adjacent segments become overloaded like this, they, too, can become damaged. How common is this? Common enough that the condition has its own name—adjacent segment disease (ASD). It can cause chronic pain, arthritis, bone spurs, and more. As it worsens your doctor may begin suggesting another fusion to address the damage the first fusion has created. And what do you think this puts you a risk for? Yes, more ASD and more fusions in the future. Though it’s important to note that even if you’ve had a fusion in the past, this doesn’t mean you have to agree to another one. In fact, agreeing to another one is likely to end in even more problems. Watch Dr. Centeno’s video below for more on adjacent segment disease:

Fusions often make the rounds on this blog as there are interventional orthopedics solutions that can help in all but the most extreme cases. Today, we are reviewing yet another study that doesn’t show favorable results for back fusion…

Three or More Levels Fused Means Nearly Three Times the Risk for More Fusions

The recent study set out to determine how often adjacent segment disease after a short fusion results in further fusions. “Short fusion” is three or fewer levels fused. They found that in those who had the maximum three vertebrae fused, there was a 2.7 times greater risk (compared to those who had two bones fused) for another fusion surgery to address adjacent segment disease that occurred as a result of the first fusion. In short, the more bones fused, the greater the risk of more fusions.

Spinal Fusion Cannot Be Undone

Spinal fusion permanently immobilizes the affected area of the spine, and neither back fusion, nor cervical fusion, can be undone. In addition to ASD, other concerns with this surgery include the following:

- Conservative approaches have been shown to be just as effective as fusion for pain and quality of life.

- Physical therapy has also been shown to be just as effective as fusion for pain as well as function.

- At two and five years following surgery, fusion patients fared no better than patients who only had a spinal decompression (or a laminectomy) surgery.

We believe that spinal fusion for the purpose of treating back pain is never a good thing and really should be avoided. While our featured study maxed at a three-level fusion, we’ve seen patients whose surgeons have fused four, five, even six vertebrae, and, unfortunately, some surgeons are routinely fusing multiple vertebrae these days. If it is clear that your case is extreme and you decide to fuse, avoid the multilevels and limit it to one or two levels at most. First, however, be sure to see your interventional orthopedic physician to make sure there aren’t indeed nonsurgical solutions, such as PRP, for your back condition. If you’re reading this and are considering a fusion, please consider instead our Perc-FSU procedure.