Is chronic neck pain preventing you from enjoying your daily life? Does your neck feel stiff and painful while working at a computer, driving, or playing with your children? Have you been told that your imaging is fine, that you just have a whiplash injury, but you know something still isn’t right? Frustrated from seeing multiple doctors without clear explanations or effective treatment options?

Perhaps you’ve even been told the pain is in your head or advised to rely on pain meds and push through. You may be dealing with an anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) injury.

After trauma, the cervical ALL ligaments can become damaged, contributing to persistent pain and instability that often goes undiagnosed. This article explores the anatomy of the ALL, common injury mechanisms, how these injuries can be overlooked, and the latest diagnostic and treatment options—including innovative approaches for ligament repair.

Anatomy of the Anterior Longitudinal Ligament

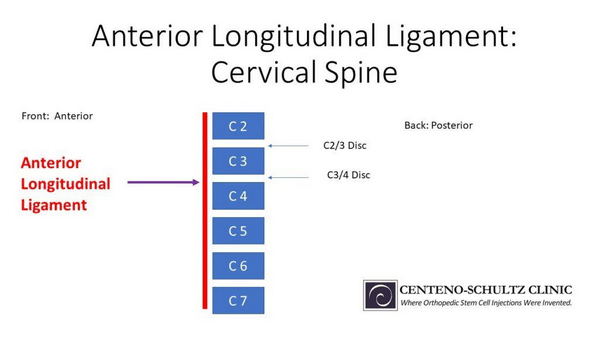

To understand the ALL, it’s helpful to review basic spinal anatomy. The spine is made up of vertebral bodies that stack on top of each other, with the cervical spine consisting of seven vertebrae. Between these bones are intervertebral discs that act as shock absorbers. The cervical spinal cord runs behind the vertebrae and discs, sending nerves through openings (neuroforamen) to the shoulders and arms to control movement and sensation.

Ligaments, like the ALL, connect bones and limit excessive motion. The ALL is a thick band running along the front of the spine, from the neck (cervical spine) down to the sacrum. It’s thicker and stronger than the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) because it’s the primary stabilizer in the front, whereas the back has several ligaments contributing to stability. This article focuses on the ALL in the cervical region.

.

Anterior Longitudinal Ligament Function

The primary function of the ALL is to resist excessive spinal hyperextension, helping to stabilize the front of the spine and support the intervertebral discs (prevents the bones from sliding backward on each other. By preventing hyperextension, the ALL reduces stress on the posterior side of the discs and facet joints in the neck, protecting these structures from injury.

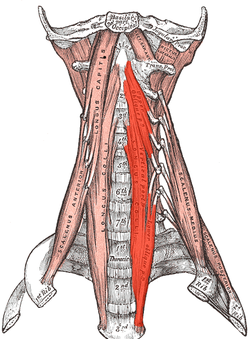

The ALL works in tandem with the longus colli muscles in the front of the neck, which help maintain posture and further prevent hyperextension. If the ALL is injured, the longus colli muscles must compensate by working harder to support the spine, leading to muscle strain or injury. In cases where the longus colli tendons are also injured, additional stress is placed on the ALL, increasing the risk of further ligament damage and instability in the cervical spine.

Signs to Watch Out for with an Injured ALL

An ALL injury can result in spinal instability, which may lead to additional complications such as disc injury, nerve irritation, spinal stenosis (narrowing around the nerves), and facet joint arthritis. The symptoms can vary based on the structures affected, the level of injury, and its severity. Common signs of an ALL injury include:

- Neck or upper back pain

- Stiffness and muscle spasms in the neck and upper shoulders

- Pain radiating down the shoulders, arms, or fingers

- Numbness and tingling in the arms and fingers

- Soreness in the neck or upper shoulder area

- Difficulty moving the neck, particularly stiffness or pain with movement

- Worsening pain with extension

- Shoulder pain

- Pain isolated to the arm, forearm, hand, or fingers

- Electric shooting sensations from the neck down through the shoulders and into the fingers

- Weakness in one or both arms, hands, or fingers

- Headaches

- Nausea, dizziness, or imbalance

In severe cases, neurological symptoms such as dysautonomia, loss of bowel or bladder control, or leg weakness may indicate spinal cord involvement and require emergency surgical attention.

Typical Cases of Anterior Longitudinal Ligament Injuries

ALL injuries can result from various types of trauma or degenerative conditions affecting the spine.

Whiplash

Whiplash occurs when the neck experiences a rapid back-and-forth movement, commonly seen in car accidents. This sudden jerking motion can stretch or tear the ALL as the head is thrown backward into hyperextension. The ligament is strained by the forceful movement, leading to pain, stiffness, and decreased range of motion.

Hyperextension Injury

Hyperextension injuries happen when the neck or back bends backward beyond its normal range of motion. This can stretch or rupture the ALL, which is responsible for stabilizing the spine during extension. Sports accidents, falls, or trauma can cause such injuries, leading to neck pain, swelling, and limited flexibility.

Compression Fractures

A compression fracture in the vertebrae can sometimes result in damage to the ALL. This type of fracture occurs when the vertebral body is crushed, usually due to osteoporosis or high-impact trauma. As the vertebrae collapse, the ALL can be torn or overstretched, particularly in cases where there is excessive spinal extension or flexion during the injury.

Degenerative Disc Disease

As discs between the vertebrae deteriorate over time, increased stress is placed on surrounding structures, including the ALL. Degenerative disc disease can cause chronic stretching or weakening of the ligament as the spine’s stability is compromised. This can lead to pain, stiffness, and even spinal deformities, particularly in the elderly population.

Diagnosing ALL Injuries

To diagnose an ALL injury, your doctor will begin by taking a detailed medical history and discussing your symptoms. A thorough physical examination is also essential, during which you may experience tenderness in the front of the neck, pain over the longus colli muscles, or discomfort with neck extension.

Imaging is crucial for diagnosing ALL injuries, but it requires careful attention since these injuries are often overlooked in standard imaging reports. As the ALL is responsible for providing dynamic stability to the spine, movement-based imaging is the most effective way to assess ligament damage.

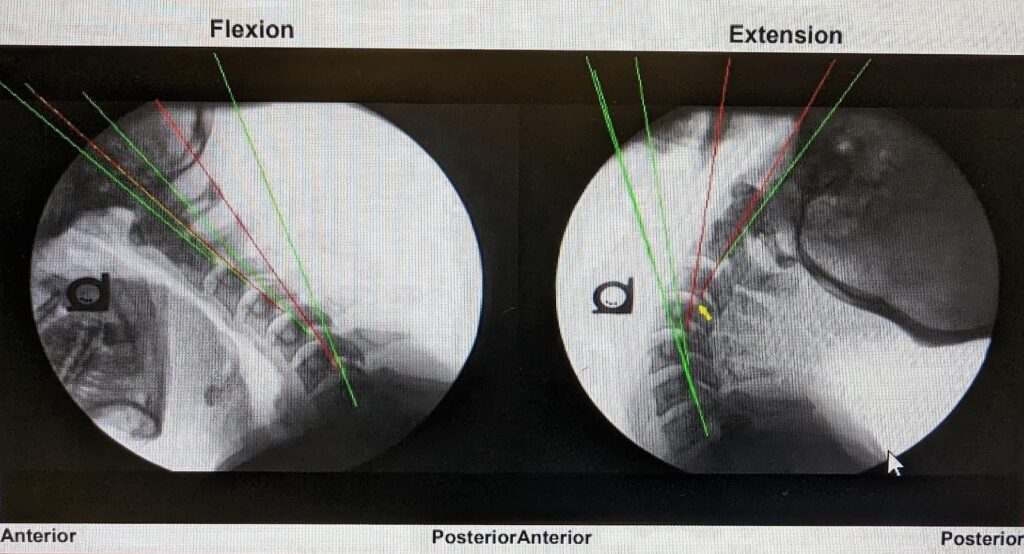

The gold standard for diagnosing ALL injuries is digital motion X-ray (DMX), or videofluoroscopy, which takes X-ray images while the patient moves in different directions. This allows doctors to measure how the bones move relative to each other—excessive movement indicates ligament injury.

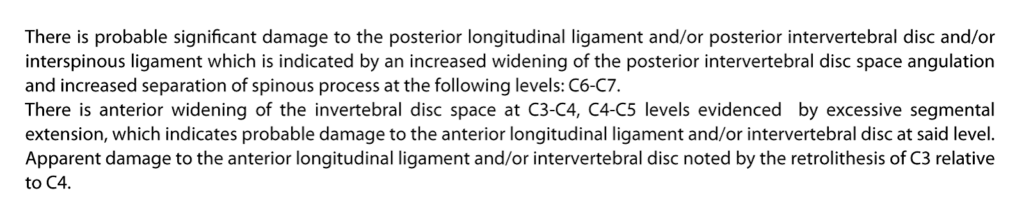

The next best imaging options are flexion-extension X-rays or a flexion-extension MRI. In a flexion-extension X-ray, a doctor can assess a widening of spaces between vertebrae during neck extension, which suggests an ALL injury. Retrolisthesis—where a bone shifts backward over the one below it—can also indicate damage to the ALL. On MRI, although it’s challenging to visualize the ALL directly, signs like swelling around the ligament or anterior disc bulging may suggest an injury.

For example, in an extension view of the cervical spine, if the C3 bone moves backward on C4, this could indicate ligament instability. In DMX abnormal extension translation of more than 2mm between vertebrae is a clear sign of ALL damage, even if it’s not immediately visible in standard imaging.

This would be a common report from the DMX.

Extension translation of the bones is abnormal if more than 2mm. So the DMX can show instability, where just visually looking at the image you may miss it.

How to Classify the Severity of the Injury

Ligament injuries, including those to the ALL, are classified into three grades based on the extent of damage:

Retracted tears, where the ligament fibers are pulled apart and often require surgical intervention for repair due to the significant loss of stability.

- Grade 1 (mild): Involves mild stretching or a small partial tear of the ligament, affecting less than 50% of its width. This typically results in minor instability and pain.

- Grade 2 (moderate): Involves a more significant tear, with over 50% of the ligament fibers damaged. This leads to moderate instability and more pronounced symptoms.

- Grade 3 (severe): Refers to a complete tear of the ligament. This can be classified further into:

- Non-retracted tears, where the torn fibers remain aligned but fully separated.

- Retracted tears, where the ligament fibers are pulled apart and often require surgical intervention for repair due to the significant loss of stability.

Conventional Treatment Options

The initial treatment for ALL injuries typically mirrors that of other neck pain conditions. Conservative measures are preferred as the first line of defense, progressing to more invasive options only when necessary. In rare cases, surgery may be the sole remaining option.

Conservative Measures

- Rest and modalities: Incorporate heat, ice, and anti-inflammatory supplements like turmeric and fish oil.

- Physical interventions: Engage in stretching, physical therapy, chiropractic care, and massage therapy.

- Medications: Utilize over-the-counter pain relievers such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Prolonged use of NSAIDs can lead to harmful side effects, as discussed in this page. Always consult with a healthcare provider before using NSAIDs regularly.

- Posture and ergonomics: Focus on maintaining good posture, neutral spine alignment, and ergonomically designed workspaces.

- Mind-body practices: Practice Tai Chi, or other alignment-focused exercises.

- Dry needling and trigger point injections: Dry needling and trigger point injections can provide effective localized relief for various injuries by targeting muscle tension and pain points. Consider these options for localized relief.

Pain Injections

If conservative treatments prove ineffective, patients may be offered steroid injections combined with a local anesthetic. While these can help identify pain sources, such as specific facet joints or nerves, they offer only temporary relief and pose risks of cartilage damage with repeated use.

Alternatively, a nerve block can temporarily inhibit pain signals from specific neck joints. This may facilitate diagnosis and, if necessary, lead to a more invasive procedure, such as radiofrequency ablation, which involves burning the affected nerve. However, like steroid injections, these approaches do not directly address ALL injuries.

Surgery

Surgery may be recommended for ALL injuries that result in disk damage and subsequent nerve impingement when conservative measures fail. The most common surgical procedure is cervical decompression and fusion.

This involves accessing the neck from the front or back to remove disk material, replace it with a bone graft or spacer, and fuse the cervical vertebrae using screws and plates. Bone spurs that compress nerves may also be excised during this procedure.

While surgery can alleviate symptoms, it carries significant risks, including infection, nerve injury, and complications related to hardware placement or fusion failure. Even successful surgeries often lead to adjacent segment disease, a condition where increased stress on adjacent disks and facets results in new pain and complications, potentially necessitating further surgeries.

Surgery is warranted primarily in cases involving spinal cord or nerve root injury, but it should be considered a last resort for pain management in most scenarios.

The Centeno-Schultz Approach to ALL Treatment

Prolotherapy

Prolotherapy involves injecting an irritant solution to create controlled microdamage to tissue, triggering a healing response. The most common solution used is hypertonic dextrose, a sugar-water mixture with a higher osmolality than the body’s tissues.

This solution draws water out of cells, inducing stress and injury, which in turn initiates a natural healing response. Although the healing response is typically modest, multiple treatments can yield significant benefits for mild ligament and tendon injuries.

Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP)

PRP therapy is derived from your own blood. The process involves centrifuging the blood to separate its components, concentrating the platelets that are rich in growth factors, cytokines, and proteins crucial for healing.

These concentrated platelets are then injected into areas of tissue injury, promoting a healing response. PRP is effective for treating mild to moderate ligament tears of the ALL and other structures.

Bone Marrow Concentrate (BMAC)

BMAC contains a wealth of healing cells, including stem cells. Similar to PRP, bone marrow is harvested and centrifuged to concentrate the healing components, which are then injected into the damaged tissue. BMAC is particularly effective for moderate to severe ligament injuries of the ALL and other structures due to its enhanced healing capabilities.

At the Centeno-Schultz Clinic, we specialize in diagnosing and treating orthopedic musculoskeletal issues, including neck pain. With 15 years of experience, we address various neck problems, such as disc, facet, ligament, and spinal nerve injuries, often utilizing the patient’s own PRP or stem cells.

In 2005, we became the first clinic globally to inject stem cells into intervertebral discs, and we have continued to consistently employ regenerative techniques like PRP and BMAC. These methods improve blood flow, reduce inflammation, and accelerate healing and repair of musculoskeletal tissues, leading to reduced pain and improved function without the risks associated with steroid injections or major surgeries.

We adopt a functional spine unit approach, treating the neck as a whole and addressing all injured structures, including the ALL, when appropriate. This contrasts with the pain generator approach, which focuses on blocking pain in one or two targeted areas through medication or nerve ablation. Our comprehensive methodology is supported by positive results in our registry data and published research.

Additionally, we have developed various interventional orthopedic procedures, documented in our textbook, Atlas of Interventional Orthopedics.

Here at the Centeno-Schultz Clinic, we have also pioneered a technique for injecting the ALL, a complex procedure that 99% of practitioners would hesitate to attempt. By combining ultrasound and fluoroscopy, we can safely inject the ALL ligaments in the C2-T1 region.

This procedure requires an extensive understanding of spinal anatomy and years of experience with guided injections to master needle visualization and spatial orientation. It’s a specialized skill not typically possessed by family doctors, orthopedic surgeons, or traditional pain specialists.

Below are some images illustrating the ALL injection.

Ultrasound image of the needle directed under the carotid artery and jugular vein towards the ALL.

Lateral X-ray (fluoroscopy image) of the needle in the ALL ligament, confirmed with contrast injection showing accurate flow in multiple sections of the ALL.

Restore Spine Wellness with Centeno-Schultz

At Centeno-Schultz, restoring spine health and function is our priority. By utilizing cutting-edge regenerative treatments and minimally invasive procedures, we aim to address the root causes of ALL injuries and other spine conditions.

Our personalized care plans focus on promoting natural healing, reducing pain, and improving mobility without the need for extensive surgery. Whether recovering from whiplash, hyperextension injuries, or dealing with degenerative disc disease, Centeno-Schultz provides comprehensive solutions to help you regain your spine wellness and get back to living a pain-free life.